Hosgeldiniz/Xwesh hatin/Welcome

2009/2010

325 images of 125 villages

Wall installation: 1300 x 160 (lh)

Table installation: 1500 x 80 x 100 (lwh)

Fotofestival Breda, Breda (NL), 2010

Biennial contemporary art Sinopale, Sinop (TR), 2010

Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerpen (BE), 2011

De Bond, Brugge (BE), 2012

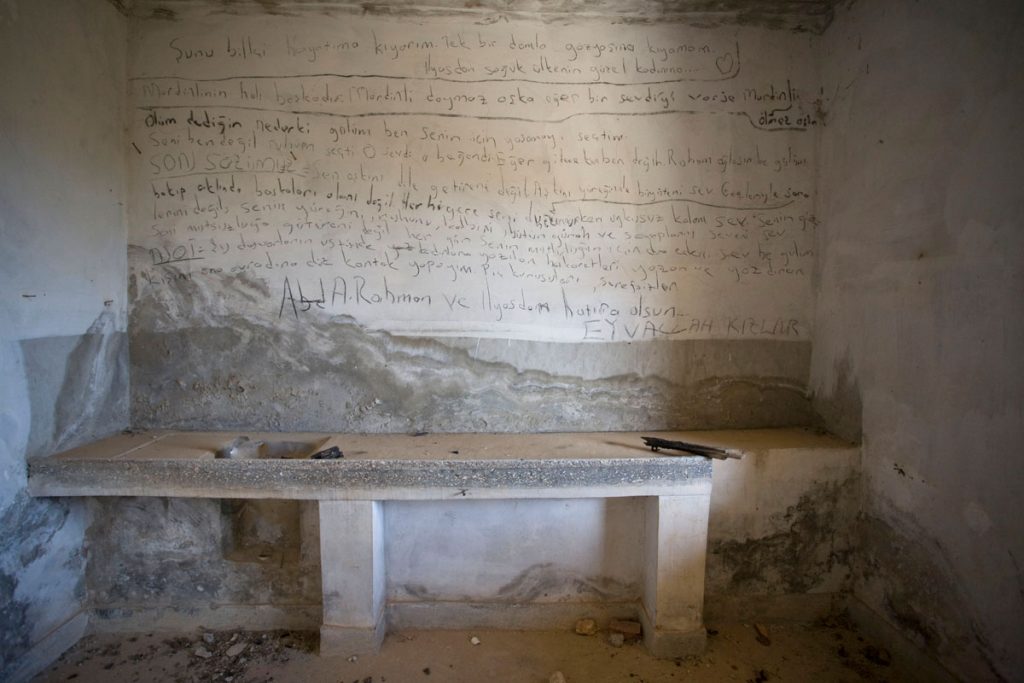

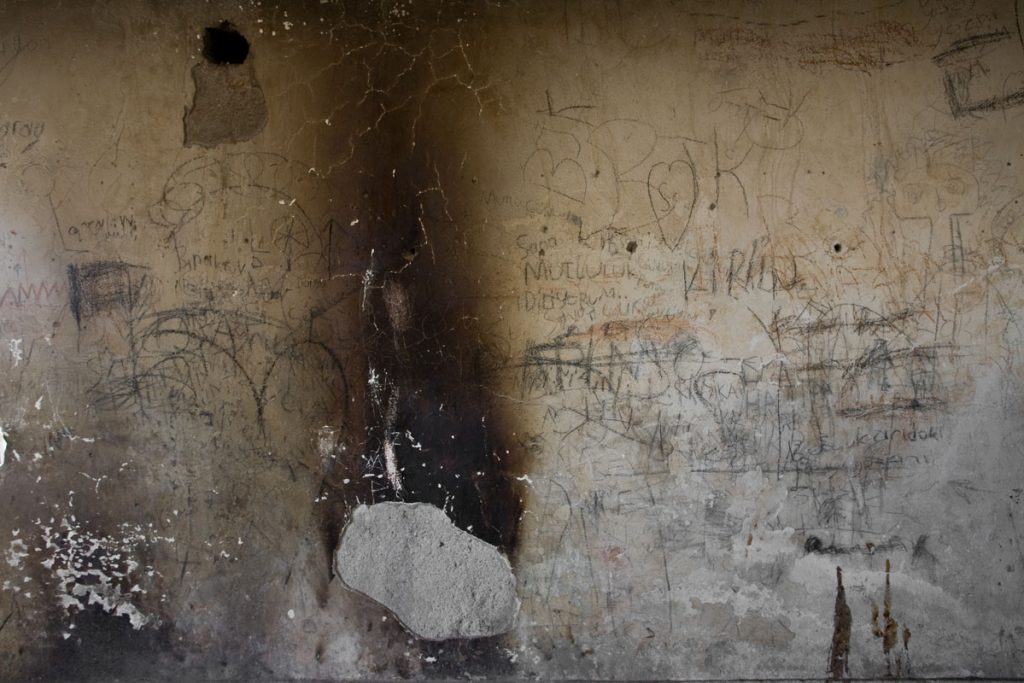

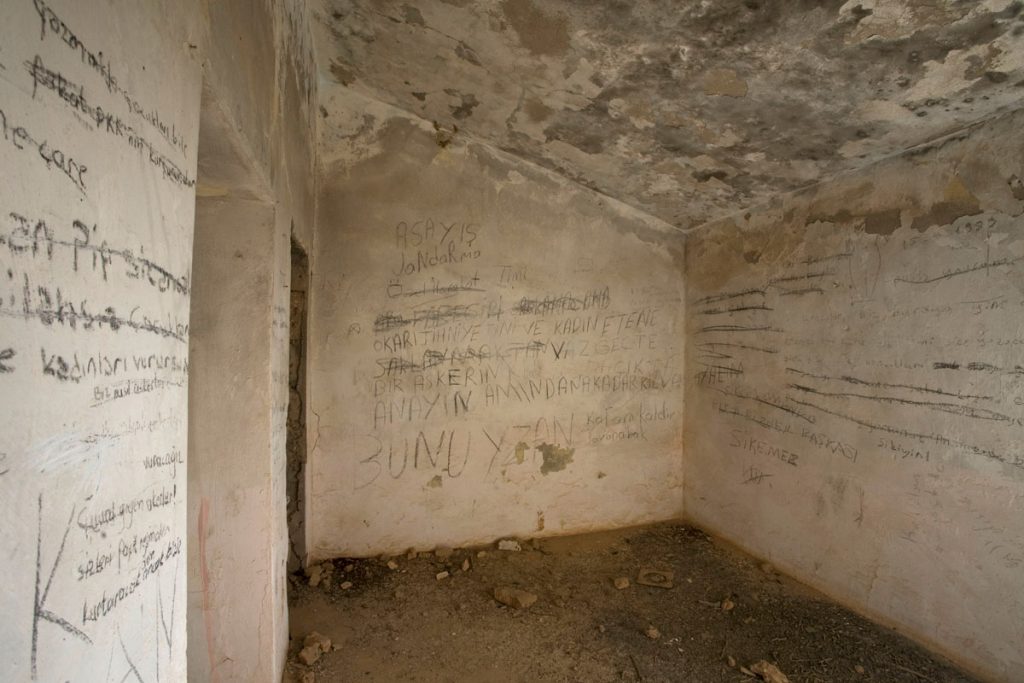

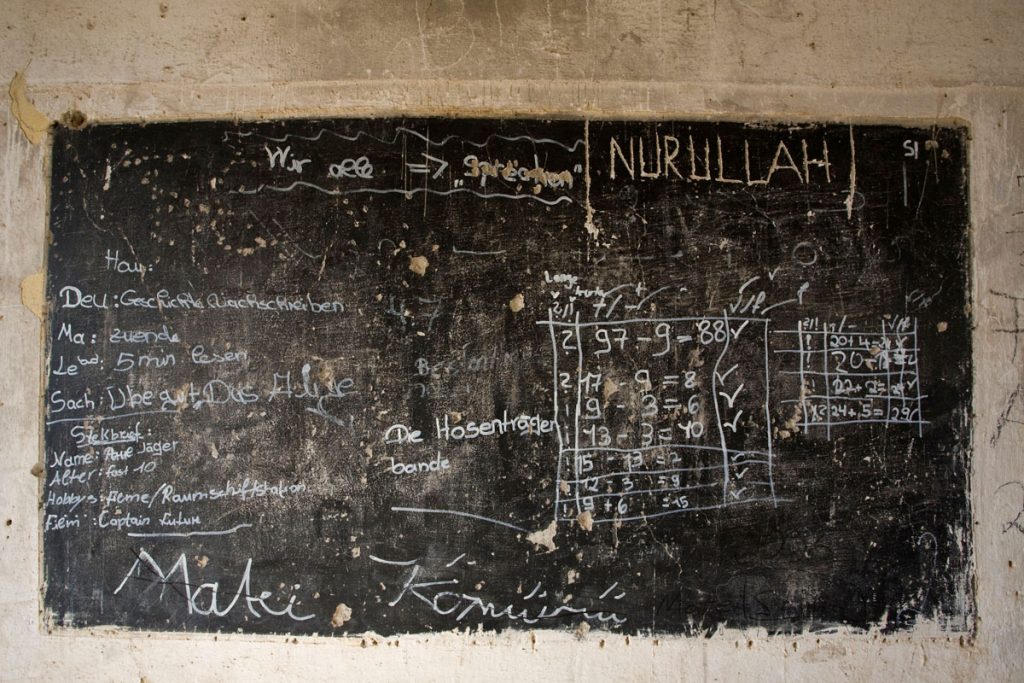

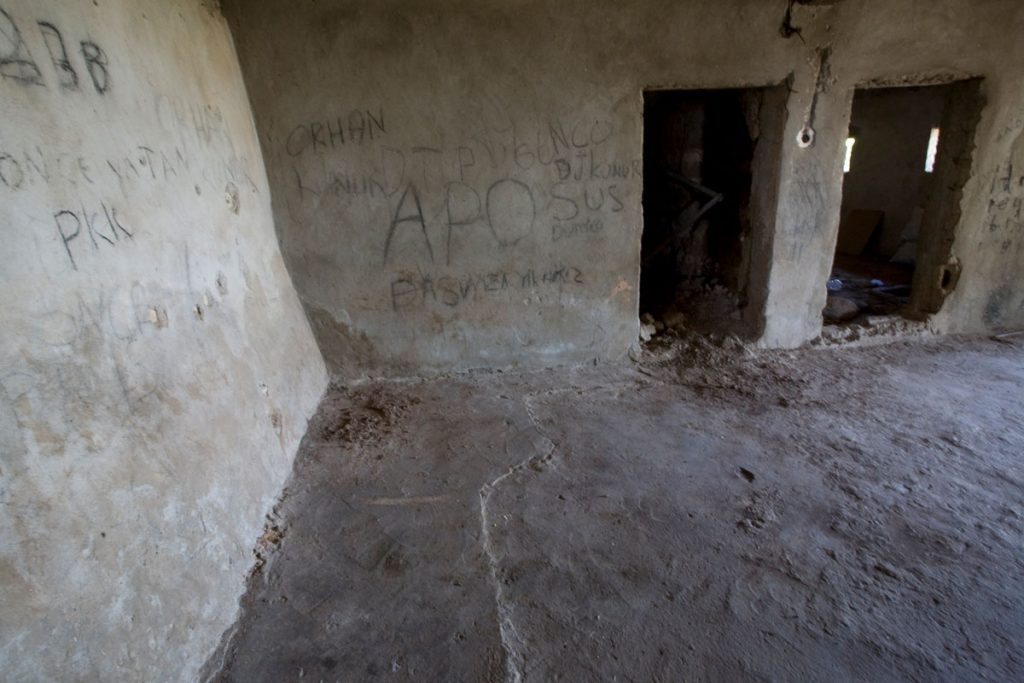

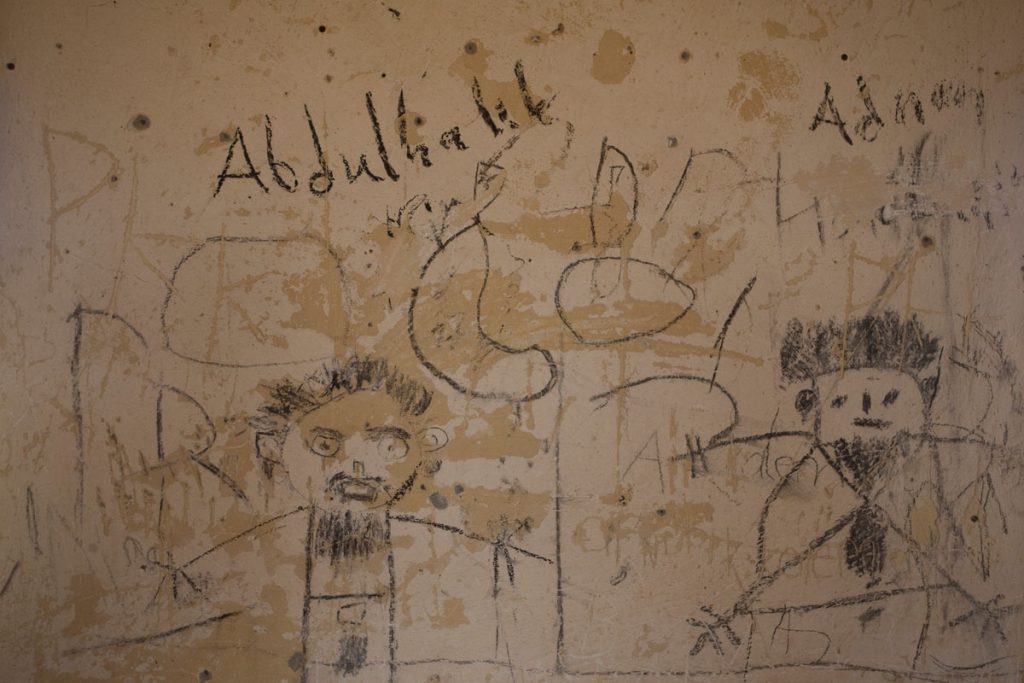

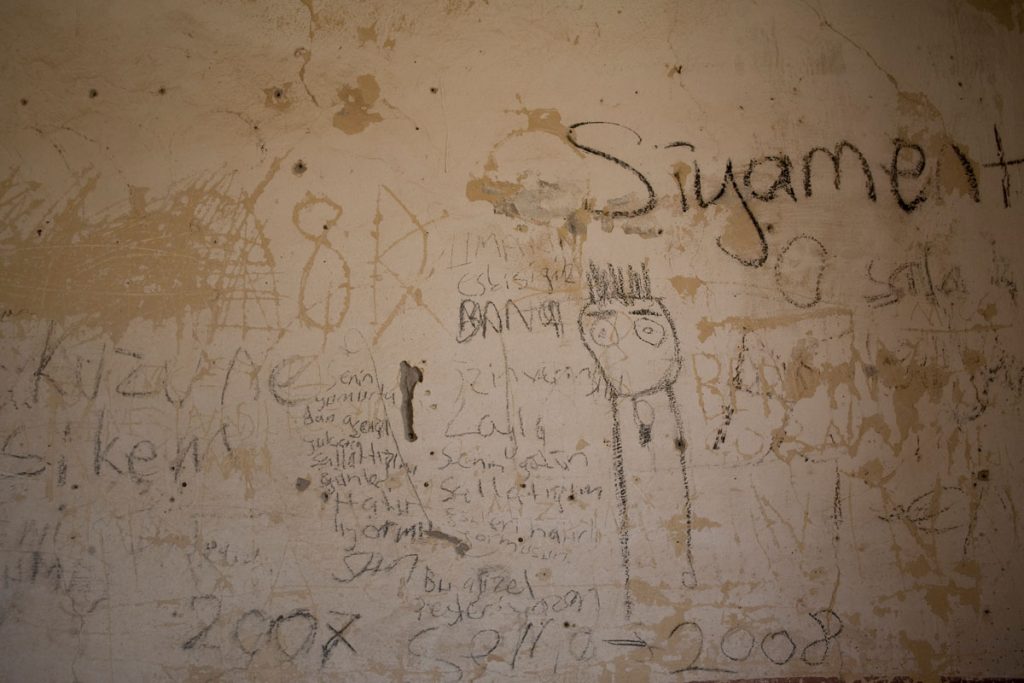

An important subject of my photographic practice in general, and of the project Hosgeldiniz in particular, is architecture as representation of shared histories or common memories. Which architectural traces, or in case of conflict: architectural ‘scars’, societies choose to preserve and which they don’t. Selecting or ignoring architectural sites is a way of defining oneself. Which image or affirmation of identity do these sites represent…? Selecting or ignoring sites is an interplay of politics and identity.

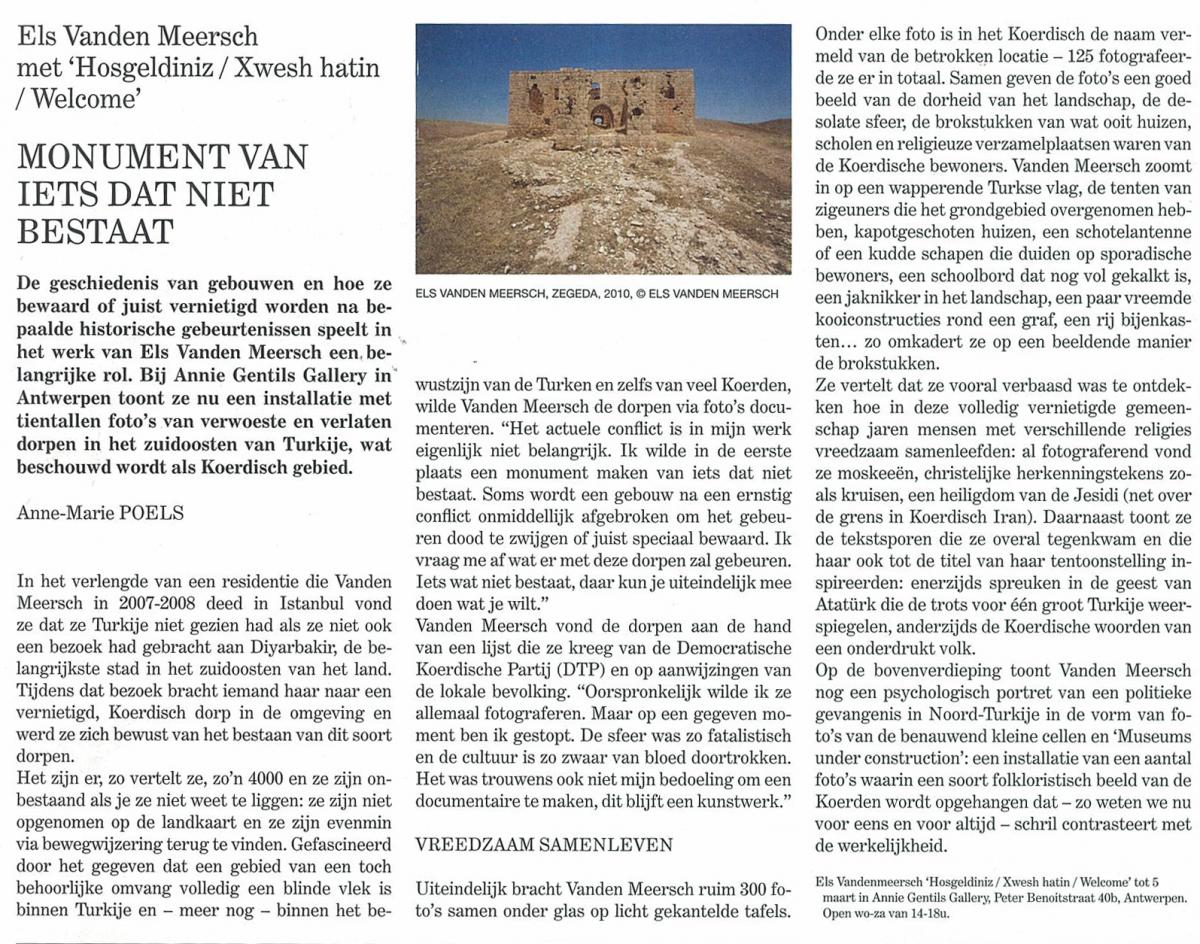

Traveling throughout the South East of Turkey is an experience of the “guilty landscape”. During the civil war of the eighties and nineties, some 3.500 Kurdish villages have been evacuated and completely or partly destroyed. The cause of the depopulation lies in the military campaign of the Turkish army, poverty in the region and reprisals of the PKK against pro-Turkish Kurds. ‘Hosgeldinis’ is a project of photographing, if possible, all these ‘ghost villages’.

The region, dotted with architectural scars, is a blind spot on the map. This is an odd fact considering our contemporary culture, in which every historical event goes along with the competition of the production and distribution of images. ‘Hosgeldiniz’ shows the ghost villages as if it were a vast archaeological site.

The project also investigates how one can photograph a recent past with the systematic style of an archaeological methodology. The pictures show the object as pluperfect, while the distinction between past and present is not yet possible. The identity-bound character of the conflict is linked to the extend of this cultural property destruction through intentional devastation, collateral damage and neglect. In many conflicts the objective to erase memories, history and traditions attached to architecture and place is a goal in itself. Identity, also the identity of minority groups, is largely designed by culture. Not in the least by architecture (shrines, social gathering places, historical places that represent myths of descent…). Cultural property is the source as well as the result of social conflicts.

Undermining cultural property, as tangible reminders, means weakening identity formation of communities.

This project wouldn’t have been possible without the support of the Flemish Community

Many thanks to the Kurdish institute of Brussels and the many persons from local villages and cities who guided me through a maze of remote places.

http://www.hosgeldiniz.be/

NOTES

Contemporary Conflict, Nationalism, and the Destruction of Cultural Property During Armed Conflict / Sigrid van der Auwera You are here

I found this clear and interesting essay on the relation between architcture, nationalism and destruction in Journal of conflict archaelogy.

An essay by:

Sigrid van der Auwera

Department of Management, Cultural Management, University of Antwerp, Belgium

ABSTRACT

During armed conflict, cultural property can be intentionally destroyed or looted. Despite the development of many preventive measures in recent decades, this phenomenon has not observably decreased. The literature on cultural property destruction during armed conflict fails to interpret this trend within a broader theoretical framework. Therefore, this article links the empirical knowledge on destruction of cultural property to contemporary theories of war and nationalism. This is achieved through an analysis of documents and literature. Our main conclusion is that the identity-bound character of (or role of nationalism in) contemporary wars is linked to an increased incidence of cultural property destruction. Moreover, factors such as illicit war economies, the prevalence of contemporary wars in weak or failed states, and the multiplicity of actors engaged, contribute to the incidence of intentional cultural property destruction and looting. These insights can contribute to an improved understanding of the phenomenon and, consequently, to an enhanced cultural property destruction prevention strategy.

Journal of Conflict Archaeology

ISSN: 1574-0773, Online ISSN: 1574-0781

Volume 7, Issue 1, pages 49-65

© W. S. Maney & Son Ltd 2012

http://www.maneyonline.com/doi/full/10.1179/157407812X13245464933821

Martelaarschap tussen Natie en Religie – Mariwan Kani

Een proefschrift dat ik vond over een paar moeilijk te doorgronden begrippen in de Koerdische cultuur.

Martelaarschap tussen Natie en Religie

Politieke liefde, poëzie en zelfopoffering in Koerdisch nationalisme

Mariwan Kani

Abstract

Mariwan Kanie bestudeerde de wordingsgeschiedenis en de veranderende betekenissen van de notie van martelaarschap binnen het Koerdisch nationalisme van het begin van de negentiende eeuw tot het einde van de twintigste eeuw. Deze geschiedenis is samen te vatten in de transformatie van martelaarschap van een mystieke en passieve vorm van lijden naar een gewelddadige activistische politieke dood voor de natie en het vaderland. Naties dwingen, net als religies, zelfopofferende liefde af. Dit suggereert dat modern martelaarschap gezien moet worden als een modern fenomeen, waarin religie geïndividualiseerd en, in een bepaald opzicht, geseculariseerd wordt. Kanie onderzocht ook de transformatie van martelaarschap in een gendercontext. In de negentiende-eeuwse Koerdische literatuur is de prototypische martelaar een man die lijdt aan een onmogelijke liefde voor een vrouw. Mannen waren dus de slachtoffers van vrouwen, meer dan de heroïsche verdedigers van een natie die zichzelf niet kan verdedigen. Met de opkomst van het nationalistische discours werd het martelaarschap in eerste instantie voorgesteld als de acties van dappere mannen die zichzelf opofferen voor een Koerdische natie, in de literatuur geportretteerd als een geliefde vrouw of een zieke moeder.

http://dare.uva.nl/record/354634

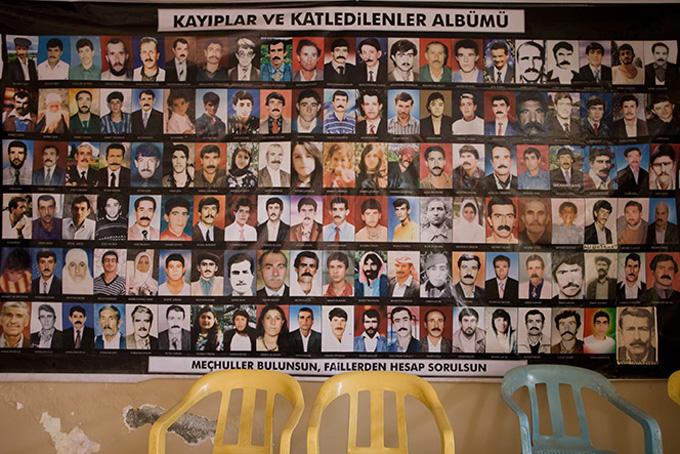

Database IHD in Diyarbakir, Turkey

The first time I was confronted with a destroyed Kurdish village was during a prospecting visit to Diyarbakir and the region in 2009. Intrigued by this visit, I started to search for pictures of other destroyed villages. The region is littered with ‘ghost villages’, but there are few photographic sources documenting this. Pictures of and by Kurds usually show folklore as their cultural identity. Plenty has been reported on the destruction of the villages, but the number of published pictures of those ghost towns does not nearly match the scale of the event. Although Turkey has been generously photographed, the south-eastern region seems to be a blind spot on the visual map. The fact that photos are so rare is remarkable in our present-day culture in which every relevant event is at the same time a battlefield for the production and distribution of images.

The first images I found were part of the collection of IHD in Diyarbakir, a small organization of human rights. These non-annotated images were compelling enough for me to start my fieldtrips.

“In the Shadow of History” / Susan Meiselas You are here

In the Shadow of History” by Susan Meiselas is a magnificent piece of work based on found footage.

“In the present work I’ve tried to re-create the Kurds’ encounter with the West and ask readers to engage in the discovery of a people from a distant place without knowing exactly where that process will lead. In no way is this a definitive history of the Kurds. Texts and images are presented as fragments, to expose the inherent partiality of our knowledge. This is a book of quotations, with multiple and interwoven narratives taken from primary sources — the raw materials from which history is constructed.”

-S.M. from “Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History”

http://www.susanmeiselas.com/archive-projects/kurdistan/#id=book_site

Exhibition at Annie Gentils Gallery, 2011